|

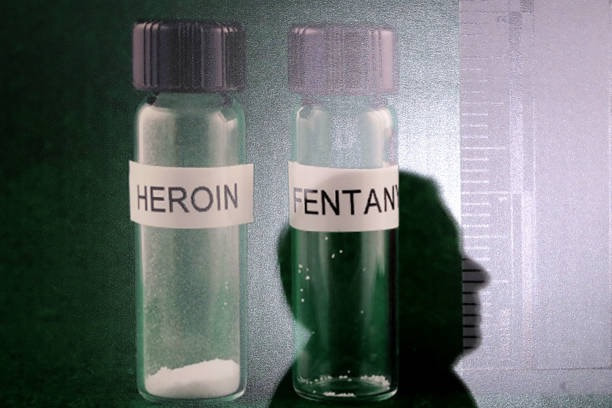

February 28, 2019 By Scottie Westfall In much of the US population, a mindset exists that we can solve severe social problems through incarceration. This idea exists because our national mindset has always been hyper-individualistic and drawn to delusions about free will. These are questions of national philosophy, and they come to the fore most obviously when we discuss the growing opioid and attendant heroin crisis in the United States. The opioid crisis didn’t arrive from Mexico. It was made in the totally legitimate pharmaceutical industry. West Virginia is thought of as the epicenter of this crisis. Coal mines and heavy industry maim people. Even if no industrial disaster befalls the worker, a life working long hours in strenuous condition can exact a heavy price on the human body. Physicians in that state were always looking for better medicines to control pain. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, oxycodone became the drug of choice to control pain, but its addictive powers were mostly under-estimated. West Virginia became known for oxycodone abuse, and the drug itself became known as “hillbilly heroin.” This drug became such a scandal that physicians began to prescribe it less frequently. However, pain management problem remained a consistent problem in much of their practices that physicians continued to prescribe various other opiate and opioid drugs. This problem was essentially ignored by the West Virginia political class. The wife of Patrick Morrisey, the state’s attorney general, is a lobbyist for major pharmaceutical companies, and she receives quite a healthy salary from companies that have profited from selling opioids to West Virginia. It was only when the extent of the problem became widely publicized that Morrisey began to distance himself from these companies. The town of Kermit in Southern West Virginia has a population of 392 people, but over two years, over 9 million opioid pills were prescribed to residents in the town. It is estimated that three large pharmaceutical companies made $17 billion selling opioids to West Virginians. A certain percentage of that profit came from legitimate use of the drugs, but most that profit came from abuse. So an attorney general, who should have been scrutinizing pharmaceuticals, was asleep at the switch, and although it is difficult to ascribe a mens rea to his lackadaisical response, it hard to see how his finances played no effect in his decision to stand down. West Virginia is the perfect place for a problem like this to get started. The economy of the state, though never wonderful, has always been tied to the fossil fuel industry. Coal mining has been dying since the 1980s, and as the coal companies have had to tighten their belts, they have warred against the unions and the pensions of their workers. With the death of the unions, the sense of solidarity died out in much of the state. Traditional American ideas, usually ascribed to the Scots-Irish character, about individualism began to metastasize in the body politic. Fewer and fewer people could find decent jobs, and the idea that this problem is the fault of the individual becomes quite pernicious when no good jobs are to be found. Poverty itself is a jagged edge. Never knowing if the rent will be paid this month or if the car can be fixed digs at one’s very soul. Further, if one must live life feeling that this insecurity is solely his or her own fault, then we have a recipe for chemical dependence. This decline in West Virginia’s economic prospects just happened to coincide with the easy access to opioids, and the disaster began. State boards of pharmacy, medical associations, and state legislatures have since taken a harder look at prescribing opioids. The easy access to the pharmaceuticals has ended, but this problem of addiction has not been solved. Those who are afflicted have turned to heroin to meet their needs, and the various illegal drug syndicates are making their money where the big pharmacies once made theirs. And after seeing that they can make money selling heroin in West Virginia, the drug has spread throughout the country. This problem is no longer one of dying coal mine towns. It is a national emergency if there ever was one. As this crisis is unfolding, we still have those who think the problem can be solved through mass incarceration. We have been incarcerating drug offenders in vast numbers since the 1980s, but the problem has not been solved. Indeed, it is worse. This same attitude that contends that humans consciously make their own fortunes leads us to the logic that if we just lock up drug offenders, they will stop using the drugs. Of course, incarceration costs lots of money, but it is a great way to warehouse people that the economy can no longer employ. It victimizes the victims more than anyone truly responsible for the crisis, be they a pharmaceutical executive or some warlord in Afghanistan with a massive poppy plantation. To solve these of problems, we would have to ditch some these ideas about individualism and free will. We would have to see that these drug crises must be solved with compassion, with effective government oversight of pharmaceuticals, and with appropriate, robust social safety nets and employment programs. But in this terminal state of neoliberalism, it is hard to see how this nation starts down a truly rational and compassionate drug policy. Big money, big propaganda, and this pernicious individualism are leaving us to rot away a whole generation of people. We will have no future unless we begin to learn from our past mistakes and determine to do something differently.

1 Comment

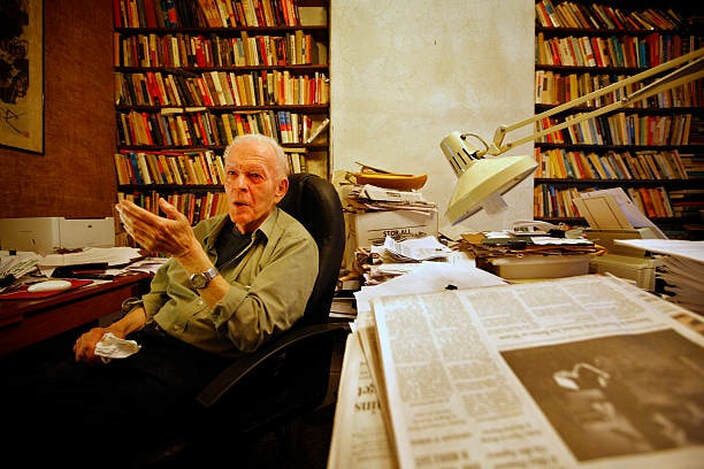

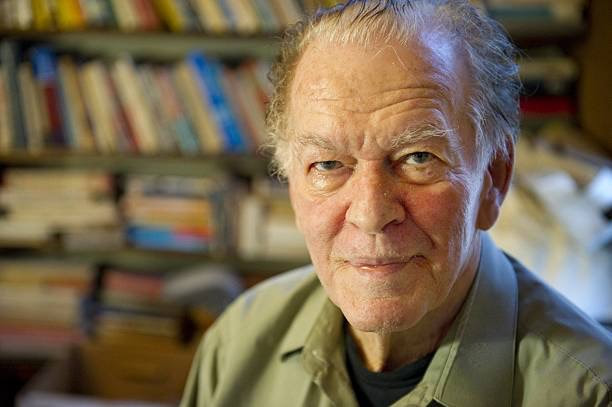

The White Rose Society honors Gene Sharp and Jamila Raqib, the Founders of the Albert Einstein Institute for nonviolent activism. Although Gene passed away peacefully in Boston, Massachusetts on January 28, 2018, he continues to inspire revolutionaries all over the world, and even the progressive organizers of the west. Today refrains like “Medicare for All,” and “We are the 99%,” are as normalized as discussions about the weather but for scholar and nonviolent activist Gene Sharp, these sentiments of equality through democracy and civilian power formed the foundation of his writing and civil work. You may not have heard of Gene Sharp. Principally he was a writer, an observer and documenter of skills to build nonviolent movements and propagated his work in books and writings, many of which are available for free on the Albert Einstein Institute’s website which he founded. His scholarship acknowledges the need for defense from those who would restrict our rights or cause us harm but highlights the moral obligation to fight back nonviolently. He reminds individuals of the Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggles provides would-be revolutionaries with 198 Methods of Nonviolent Protest for Civilian-Based Defense from tyrannical leaders who seek to deprive people of their rights. Sharp’s true legacy, however, rests in the influence of his teachings on the real struggle against tyranny. His work is credited to be the foundation for the Arab Spring uprising and the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević, the former pro-Serbian, nationalist dictator of Yugoslavia. When asked about this influence, he declines any credit or paternalist influence saying to the New York Times in 2012: “I don’t talk about what needs changing or where. It’s up to the people themselves who decide to change.” Reclaiming power in an environment of fear It’s a common misconception of each new generation that the present represents the most dangerous, or the least free period in history. Sharp, born at the start of the Great Depression, witnessed the rise of fascism, nuclear annihilation associated with the Second World War, and lived under the threat of the Cold War for much of his youth. Sharp refused to be cowed by fear of hostile governments. Instead, he focused on their role as power brokers in a global society and those individuals who successfully wrest power away from the elite. Some of those people, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. were loci of how power can shift non-violently and informed Sharp’s case studies of nonviolent revolutions. He never sought to begin the revolution instead, he said, “I’m trying to examine how nonviolent struggle has been operated. And sometimes it fails for a while, sometimes it succeeds. But how can you wage nonviolent struggle more skillfully while using your mind to plan?” And the Oscar for peaceable regime change goes to... Gene Sharp! Arab Spring leaders utilized Sharp’s book From Dictatorship to Democracy, which was written at the request of dissidents in Burma and originally published there. It is a guidebook for revolutionaries to understand how to organize and create their own power. Today, it is published in 31 languages. This same book also influenced Otpor! the main group opposing Miloseviç during the Serbian uprising. These revolutionaries were even trained by Sharp at the Albert Einstein Institute. What differentiates Sharp from his contemporaries and other civil disobedience actors was his adherence to post-colonial, or anti-paternalistic, international relations theory. What else can we learn from Gene Sharp? Throughout the 20th century, regime change was principally led by western governments seeking to impose democracy or depose dictators. In these instances, elites are the nexus of power in the hope that new, western-aligned, elites can bring democracy and human rights to nations that had previously been subjugated. For Sharp, protests, revolutions, and regime change are principally methods to reorganize the power structure and remind elites that without the support of the people, their regimes might cease to exist in an instant. Post-colonialism is principally how victims of paternalism reclaim their power and nations from colonizers. Today, in one of the most unequal periods in history, progressives across the west, like their Middle Eastern, Southeast Asian, and Eastern European counterparts before them, are organizing, following the principles of 198 Methods. “When power is effectively effused throughout the society among strong loci,” where loci is defined as civil society groups who hold sway over social and political happenings, “the rulers’ power is most likely subjected to controls and limits, thus enabling the society to resist oppression, usurpation, and aggression. This condition is associated with political freedom.” For modern progressive activists, Sharp’s work is more significant than ever before. Across the west, elites have consolidated power at the expense of the many. We are beginning to see the majority organize against tyrannical power. “People continue,” he said to the NYTimes, “because it works. When you start withdrawing your cooperation, the regime won’t like it. They will instill fear, but if you are not afraid, then the reason for fear does not exist.”  Peacemaker Author: Jessica Adams Peacemaker Author: Jessica Adams How to Avoid Accidental “Triggers” on Social Media By Jessica Adams Emotions are tricky beasts. They often arrive uninvited and leave without saying goodbye. They can also make for some challenging communication when they cloud our thinking. Thankfully we humans have taken the time to understand what emotions are--and what they are not. But sometimes we get it wrong. Most of us know that our emotions are not reflections of the real world, that how we feel about a person does not necessarily mean that we truly understand them. How often have we misjudged a person? More often than most of us will admit. Sometimes our emotions trick us into believing things of others that may not be true. This can make for some difficult challenges in our world of digital communication where all we can see of each other is the exchange of words. In the realm of Nonviolent Communication (NVC), often called compassionate communication, a distinction is made between emotions and evaluations. For example, fear, worry, love, concern, joy, sadness, and serenity can all be identified as emotions. But there are other things that we say we “feel” that aren’t genuine feelings. To say, “I feel abandoned” is to place an evaluation on others, according to NVC experts such as Dr. Marshall Rosenberg. In his book Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life, Dr. Rosenberg says, “What others do may be a stimulus of our feelings, but not the cause.” Perhaps a person feels lonely. Those around them have gone, and our person is alone. If our person says, “I feel abandoned,” they are not expressing a true emotion but an evaluation of the motivations of others. Our person may feel sad, lonely, depressed, or any number of other things, but they can’t feel abandoned because it presupposes the intentions of others. If I tell you that I feel cheated, then I have essentially declared that a person has tried to cheat me. Whether you are messaging with your spouse, coworker, or someone of an opposing political party, using even mildly inflammatory language that evaluates another person’s motivations and behaviors is far more likely to trigger an antagonistic response, derailing the process of peace building and creating barriers in communication. When you are sharing your feelings online, remember to use “I feel…” statements, but also be sure that your feelings are just that--feelings--and not reflective of thoughts or stories. You will find that communication flows more smoothly when the language you use is free of blame or evaluation of another person’s motivations and behaviors. You are your own vehicle for peacemaking in daily life. The next time you find yourself needing to share your emotions with others, do a simple check: is this a genuine expression of emotion, or am I including thoughts and stories in my statements of feelings? Peace be with you! American Immigration Sideshow: Border Wall or Distraction? By Scottie Westfall As we enter this new conflict over the national emergency declaration at the border, much of the discussion has been framed over its constitutionally. Yes, real issues exist with the “imperial presidency,” but that problem is decades old. Presidents have used power to deflect from scandal before, and congress has abdicated one power after another to the presidency. These issues, although certainly a long-term problem with this constitutional system, are largely overshadowing the real crisis of migrants seeking refugee status. Trump is hardly the first president to get into this situation about border security. During 2011 and 2012, Barack Obama and then Arizona Governor Jan Brewer exchanged some well-publicized exchanges over the building of a border fence. In the May of 2011, Obama bragged that the border fence was “basically complete,” which led to large numbers of right-wing populists calling foul. Obama was hardly a saint when it came to undocumented migrants. He oversaw the deportations of 2.7 million people, and for a time during the 2016 presidential election cycle, he was denounced by some immigration activists as the “deporter-in-chief.” Both the Trump and Obama administrations face the same refugee crisis. The Central American nations of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, long the home of all sort of US imperialist intrigue, are lands of violence. Gangs, which are essentially paramilitary organizations operating the way crime syndicates do, are wreaking havoc upon civil society in these countries. Escape to Mexico or maybe the United States is a very real existential hope for so many people. Establishing asylum really does mean the difference between death and survival. A great hope once existed in Central America. In 2006, Honduras elected a reformer named Manuel Zelaya to the presidency. He was not a fire-breathing socialist like Hugo Chavez in Venezuela or Lula in Brazil. He was a rancher who had been elected on a centrist platform, but as president, he switched to the left, increasing the minimum wage, making education free to all children, and providing some state aid to the poorest of the poor. He was ousted in 2009. Then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made no quibbles when the Honduran military removed him from office. Violence swept through Honduras, as she covered for the coup, and in 2014, when tens of thousands of unaccompanied minors arrived at the US-Mexican border, she callously called for the deportation. “We have to send a clear message that just because your child gets across the border doesn’t mean your child gets to stay,” she said then. Flash forward into the current presidency, and now immigration policy is but a sick burlesque. In the summer of 2018, the Trump administration experienced a similar crisis with Central American migrants. This time, many migrants came as full families, and the US put on such a display of utter cruelty, pulling young children away from their parents and holding them in dentition centers. In December of that year, the US was holding 15,000 minors in its custody and was struggling hard to reunite them with their parents. That same month, two children have died in US custody, sparking requests for an inquiry. But so much of that disgusting episode has been lost in the current national emergency debacle. We have somehow forgotten that people are suffering and dying. Children are being traumatized through these horrific separations. Our leader plays head demagogue about every “caravan” of migrants that begins working its way up through Mexico. In a more sedate time in US politics, politicians engaged in dog whistle politics. They mentioned “welfare queens” to scare blue collar voters that their tax dollars were going to African American women who didn’t work but were able to buy all sorts of extravagances drawing the dole. But now, they make no attempt to hide their racism. Donald Trump started his presidential campaign lambasting Mexican rapists. He now hits the fears of Latino drug dealers as hard as he can. In places where the opioid crisis has claimed a whole generation, such as West Virginia and Ohio, the fears of drugs are very real, but Trump uses that terror to gin up the most insatiably rabid form of xenophobia. This rabid xenophobia is a potent tool to keep the base on his side as a new election cycle looms ahead. Various investigations could also be hazardous to his power, so it is politically expedient to generate hate and keep it burning red and hot. But we still have a political system that has forgotten the poor and the suffering. Those who mourn their family members’ drug dependency receive no real relief from the federal government, and the migrant children have had their whole world uprooted. These are the people who need compassion the most, yet we are lost in the disgusting burlesque of a government shutdown and a zany national emergency declaration.  Peacemaker Magazine Writer: J.A. LLOYD Peacemaker Magazine Writer: J.A. LLOYD White Rose: The Farewell and New Beginning By J.A. Lloyd The White Rose (also known as weisserose) Revolt dates back to the summer of 1942 when a group of young individuals formed a non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. The group became known for an anonymous pamphlet campaign that called for opposition against the Nazis regime. Over 75 years later we see the need for resistance once more. We are not so naïve as to believe that with the fall of Nazi Germany hate and prejudice fell with it. In fact, we are quite aware of its ever-present existence and are appalled to see it rising to the forefront once more with our current leaders and their imbalanced world views. There is a simple fact that we cannot ignore which is a direct reflection of humanity’s current state: hate crimes are on the rise. A look at 10 of America’s largest cities offers a glimpse into the ascent beginning in 2017, shortly after our current president took office. Likewise with the rise of social media also comes a new platform—the digital landscape in which messages of varied forms hate, bigotry and racism are given the power to reach audiences like never before. And we believe it’s impossible to condone the severe spike in both hate and prejudice spurred on by the incivility of national events. With our current president, we’ve seen an executive order provisionally barring refugees and citizens of chiefly Muslim countries from entering the United States. This came shortly after another executive order approving construction of a wall along the Mexico border. We understood these messages, along with countless others our president has tweeted: you are not welcome. You are less than. We’ve heard the prejudice, discrimination, and hatred and we see the blatant rise of disregarding individuals because of their national origin, ethnicity, or color. We disagree with these messages. The White Rose Society of the 21st century is a vast network of people with diverse backgrounds who share the goal of creating solutions that work for all of humanity. Our authority is truth, and our only rule is non-violence. We do not discriminate against anyone because of race, caste, color, creed, religion, gender, sexual preference, nationality, political affiliation, socioeconomic status, career or other reasons not mentioned here. All are welcome. We stand behind words, not weapons. We believe open conversations aid national issues more than violence ever will. We encourage the promotion of tolerance and compassion and believe that the solution to this problem starts with a civil dialogue between both sides. |

AuthorPeacemaker Magazine is a White Rose Society publication. Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed