|

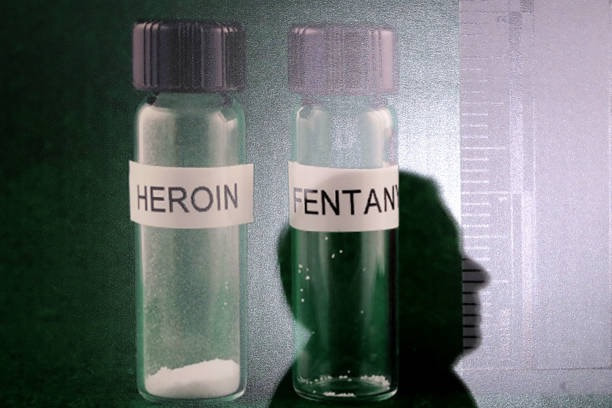

February 28, 2019 By Scottie Westfall In much of the US population, a mindset exists that we can solve severe social problems through incarceration. This idea exists because our national mindset has always been hyper-individualistic and drawn to delusions about free will. These are questions of national philosophy, and they come to the fore most obviously when we discuss the growing opioid and attendant heroin crisis in the United States. The opioid crisis didn’t arrive from Mexico. It was made in the totally legitimate pharmaceutical industry. West Virginia is thought of as the epicenter of this crisis. Coal mines and heavy industry maim people. Even if no industrial disaster befalls the worker, a life working long hours in strenuous condition can exact a heavy price on the human body. Physicians in that state were always looking for better medicines to control pain. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, oxycodone became the drug of choice to control pain, but its addictive powers were mostly under-estimated. West Virginia became known for oxycodone abuse, and the drug itself became known as “hillbilly heroin.” This drug became such a scandal that physicians began to prescribe it less frequently. However, pain management problem remained a consistent problem in much of their practices that physicians continued to prescribe various other opiate and opioid drugs. This problem was essentially ignored by the West Virginia political class. The wife of Patrick Morrisey, the state’s attorney general, is a lobbyist for major pharmaceutical companies, and she receives quite a healthy salary from companies that have profited from selling opioids to West Virginia. It was only when the extent of the problem became widely publicized that Morrisey began to distance himself from these companies. The town of Kermit in Southern West Virginia has a population of 392 people, but over two years, over 9 million opioid pills were prescribed to residents in the town. It is estimated that three large pharmaceutical companies made $17 billion selling opioids to West Virginians. A certain percentage of that profit came from legitimate use of the drugs, but most that profit came from abuse. So an attorney general, who should have been scrutinizing pharmaceuticals, was asleep at the switch, and although it is difficult to ascribe a mens rea to his lackadaisical response, it hard to see how his finances played no effect in his decision to stand down. West Virginia is the perfect place for a problem like this to get started. The economy of the state, though never wonderful, has always been tied to the fossil fuel industry. Coal mining has been dying since the 1980s, and as the coal companies have had to tighten their belts, they have warred against the unions and the pensions of their workers. With the death of the unions, the sense of solidarity died out in much of the state. Traditional American ideas, usually ascribed to the Scots-Irish character, about individualism began to metastasize in the body politic. Fewer and fewer people could find decent jobs, and the idea that this problem is the fault of the individual becomes quite pernicious when no good jobs are to be found. Poverty itself is a jagged edge. Never knowing if the rent will be paid this month or if the car can be fixed digs at one’s very soul. Further, if one must live life feeling that this insecurity is solely his or her own fault, then we have a recipe for chemical dependence. This decline in West Virginia’s economic prospects just happened to coincide with the easy access to opioids, and the disaster began. State boards of pharmacy, medical associations, and state legislatures have since taken a harder look at prescribing opioids. The easy access to the pharmaceuticals has ended, but this problem of addiction has not been solved. Those who are afflicted have turned to heroin to meet their needs, and the various illegal drug syndicates are making their money where the big pharmacies once made theirs. And after seeing that they can make money selling heroin in West Virginia, the drug has spread throughout the country. This problem is no longer one of dying coal mine towns. It is a national emergency if there ever was one. As this crisis is unfolding, we still have those who think the problem can be solved through mass incarceration. We have been incarcerating drug offenders in vast numbers since the 1980s, but the problem has not been solved. Indeed, it is worse. This same attitude that contends that humans consciously make their own fortunes leads us to the logic that if we just lock up drug offenders, they will stop using the drugs. Of course, incarceration costs lots of money, but it is a great way to warehouse people that the economy can no longer employ. It victimizes the victims more than anyone truly responsible for the crisis, be they a pharmaceutical executive or some warlord in Afghanistan with a massive poppy plantation. To solve these of problems, we would have to ditch some these ideas about individualism and free will. We would have to see that these drug crises must be solved with compassion, with effective government oversight of pharmaceuticals, and with appropriate, robust social safety nets and employment programs. But in this terminal state of neoliberalism, it is hard to see how this nation starts down a truly rational and compassionate drug policy. Big money, big propaganda, and this pernicious individualism are leaving us to rot away a whole generation of people. We will have no future unless we begin to learn from our past mistakes and determine to do something differently.

1 Comment

|

AuthorPeacemaker Magazine is a White Rose Society publication. Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed